Posted 25/2/2014

Weimar Out, Nazis In

Robert Liebman

For British novelist Christopher Isherwood (1904-86), Berlin during the Weimar era had its attractions. Then Hitler arrived.

In 1929, Isherwood moved to Berlin, lived in rented rooms, taught English to support himself, and kept a diary which served as the basis for his short-story collection Goodbye to Berlin (1939). The publication date is deceptive. The book was effectively written in the early 1930s before Hitler became Chancellor but while the Nazis were rising in power—and, a feral force, roaming the streets. Isherwood captures the ethos of a German capital undergoing massive change. By the time (January 1933) Hitler became Chancellor, Isherwood’s Berlin sojourn was effectively over.

The political situation in Germany is not what lured Isherwood to Berlin. It was the capital’s nightlife, its bars and clubs. It was “boys.” London was not devoid of young men, but Isherwood felt freer in the German capital.

He found what he came for, but when Hitler became Chancellor, Berlin’s mood rapidly darkened and he returned to England. Later, he became a successful screenwriter in America.

Heavily Factual Fiction

Goodbye to Berlin is actually a compilation of six loosely linked semi-autobiographical stories covering the period before the Nazis assumed control of the government.

Don’t be misled by the 1939 publication date. Although published in the same year that the Second World War began in Europe, the experiences the author draws on occurred before Hitler came to power early in 1933. The conflagration at the Reichstag, the remilitarization of the Rhineland and Kristallnacht had not yet occurred. Jews were tormented by Nazi thugs even before Hitler became Chancellor, but the Holocaust wouldn’t begin in earnest for another decade. Isherwood is recording late Weimar Berlin, not post-Hitler Germany, and this time frame lends the novel its value as a window into pre-Holocaust Germany.

Before becoming Chancellor, Hitler was unable to give a green light to his police, whether secret or not, to harass the Jews. Nevertheless, Brownshirts were on the streets, thugs doing what thugs do. Jews, frequent targets, were scared, but also complacent. This is the ambience of Isherwood’s Berlin, made more relevant by his characters being closely based on actual people. He is not bound by facts, and he makes things up, and alters even critical details, if the changes will enhance the narrative. But his characters are, for the most part, real, and realistically portrayed.

One of the tenants in Isherwood’s rooming house is a Nazi, a fact that elicits nothing stronger than mild disapproval from the other lodgers. Indeed, the novel opens with the author’s famous declaration regarding his writing technique: “I am a camera with its shutter open.” He is a neutral observer, reluctant to provide much commentary or judgement.

Isherwood the English-language teacher in Germany had two Jewish pupils who he incorporated into his book. Hippi Bernstein is interested in almost everything else except learning English. Invited to lunch with her family, Hippi’s mother notes that Jews are being harassed. Hippi’s father is dismissive: “Ach, what does that matter? If they throw stones at you, I will buy you a sticking-plaster for your head. It will cost me only five groschen.”

Through Natalia Landauer, another Jewish pupil from a wealthy family, Isherwood met her cousin Bernhard Landauer, who manages his family’s large department store. Isherwood’s recounting of Bernhard’s life reaches into the early months of the Nazi era, a time when Isherwood no longer had direct contact with Bernhard. But the businessman was prominent, and Isherwood relied on information he received about Bernhard after he lost direct contact with him. By this point in time, danger for Jews had seriously escalated.

Sally Enters this Frame

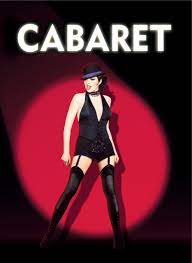

Sally Bowles is best known thanks to Cabaret, the 1972 film directed by Bob Fosse and starring Liza Minelli. Her story is the longest of the six and was published as a stand-alone novella in 1937 by Virginia and Leonard Wolff’s Hogarth Press.

In the book, Sally complains that one of her lovers is “an awful old Jew.” Otherwise her story contributes almost nothing to the political side of, or Jewish interest in, Goodbye to Berlin. But her real-life model, Jean Ross, had extensive Jewish connections.

Fictional Sally is all of 19 years old, chases fame, men and money, and has no interest in politics.

Jean Ross (1931-1973)

Jean Iris Ross—Jean Cockburn after she married Claud Cockburn— was a deeply committed Communist, as was her husband. They had five children who also became noted radical writers and activists. One of the five, Alexander Cockburn, was closely linked to, and often had intense disagreements with, Christopher Hitchens, a prominent essayist who notably hammered both Mother Teresa and Henry Kissinger. Hitchens was not Jewish (his first name is a giveaway) until his mother, well into his as well as her own adulthood, admitted that she was actually Jewish.

Before marrying Cockburn, Ross was involved with Birmingham-born Albert Eric Maschwitz, son of a Russian Jew (Wikipedia says that he was a “descendant of a traditional German family”) and composer of the jazz classic “These Foolish Things Remind Me of You.” Yes, that Albert Eric Maschwitz, husband of actress Hermione Gingold. According to some sources, Jean Ross was the inspiration behind his famous song.

*

Isherwood’s Christopher and His Kind (1977) provides updates on several of the characters who appeared in Goodbye to Berlin. Remarkably, all of them seem to have survived the war. However, the real-life model for one of the major characters succeeded in fleeing Germany in time only to be killed in the same wartime plane crash that took the life of Jewish actor Leslie Howard.

Isherwood was close to poets WH Auden and Stephen Spender, both from, as he writes, “partially Jewish” families, and he moved in largely Jewish circles, not always happily or admiringly, as a successful screenwriter in Hollywood.

Jean Ross died in Richmond, southwest London in 1973.

Sally Bowles is still going strong.

[END]

Copyright © 2024 Robert Liebman. All Rights Reserved