Schemers and Dreamers, Ids and Yids

In October 1947, a Jewish-American writer, grandson of a Russian rabbi, completed page 721 of his 721-page novel and set off for a year in Paris with his wife. First novel. First wife.

His novel, published while he was in the French capital, met with widespread acclaim and he started a new novel, which he completed after returning home to New York. Short where his first novel was long, symbolic instead of realistic, and with a skimpy contrived plot, novel number two fell flat on its face.

When he died at the age of 83, his totals were ten novels, six wives and numerous awards—but the gong he yearned for most eluded him.

In September 1948, another young Jewish-American writer (the born-in-Canada variety), also the grandson of a Russian rabbi, went to Paris with his first wife. He already had two accompished but modest novels under his belt and was well into his third. He never finished it. Instead, he abruptly ditched it and started an entirely new work which he completed after returning to America several years later.

His original third novel, the one he jettisoned, would have been in the same competent but dreary league as his previous novels. His new work was a different species altogether, stylistically as well as in subject matter. It provided him with a lush new vein and he mined it to the hilt. When he died, aged 95, his tally was 13 novels, a mere five wives, and one Nobel Prize.

The futures for both writers turned on the novels they started in Paris, but why did this most inspirational of cities prove poisonous for one of them and magical for the other?

Dream Debut

Couple number one: Norman Kingsley (Nachman Moloch [King in Hebrew]) (1923-2007) and Beatrice Mailer (née Silverman).

Novel number one: The Naked and the Dead, his war novel set on a tropical Pacific island. He followed up with Barbary Shore (1951), a political thriller set in a Brooklyn rooming house. Short and symbolic where his war novel was long and naturalistic, his peacetime novelhas one-dimensional characters, a flimsy plot and abstruse, unappealing subject matter. Kind reviewers panned it, unkind reviewers savaged it, and book-buyers didn’t buy it. Even his publishers disliked it.

Was Barbary Shore nothing worse than a bog-standard second-novel wobble, a temporary setback for an obviously talented and politically engaged writer? Or was his precocious war novel the fluke? Basically, was he any good as a novelist?

Time would tell. It did.

Hydrotherapy

A few weeks after the Mailers returned to New York, Saul Bellow (né Solomon, a.k.a. Shloime and Shloimke, 1915-2005) and his wife Anita (née Goshkin) embarked on a multi-year European Grand Tour which included a lengthy stay in Paris.

His first two novels, Dangling Man (1944) and The Victim (1947), made Bellow a household name—in houses that subscribed to heady periodicals like Partisan Review. After these two competent but glum novels, he set his next work in a hospital, apparently intent on making it three in a row.

He was rescued by the Mother of all Epiphanies. Walking to his office one sunny morning, he became transfixed by the rivulets of water coursing along the curb, a daily Parisian street-cleaning ritual.

Sacre dieu! I can write like that water, free-flowing, going who knows where. He could and promptly did, immediately binning his hospital novel and starting an entirely new work in an entirely new style and with a new kind of hero.

Call him Augie.

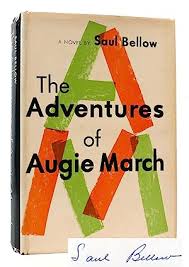

Exuberant instead of stodgy, The Adventures of Augie March (1953) won the National Book Award, ended its author’s obscurity, and was the gift that kept giving.

Augie begat Seize the Day (1956), which begat the African explorer Henderson the Rain King (1959), which begat Herzog (1964) and the holocaust survivor of Mr. Sammler’s Planet (1970), all combining with other novels, novellas and short stories to begat the 1976 Nobel Prize. A dab of eau de Paris went a long way.

Mailer Marches On

Mailer entered Harvard as an engineering major and exited determined to become a “major writer.” He fantasized writing a twenty-volume behemoth that would “out-Joyce James.” He would be “the greatest writer of this decade,” the 1940s of Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner.

He enjoyed an ideal launch with his realistic first novel and, to demonstrate his versatility, he switched to symbolism in his next effort. He also strove to make it “perfect” to compensate for its relative brevity.

It wasn’t.

What went wrong?

Just about everything.

Barbary Shore is narrated by Mike Lovett, an aspiring writer and Trotsky supporter lodging in Mrs. Guinevere’s boarding house. Although afflicted with amnesia, he remembers and recites his Marxist catechism in considerable detail.

Guinevere is secretly married to another Trotskyite tenant, McLeod. She is buxom, frivolous, flirtatious and apolitical. He is a powerful revolutionary leader on the run, stalked by another tenant, a government agent.

Their daughter Monina is a preternaturally precocious three-year-old mini-monster, and another Trotskyite lodger, Lannie Madison, is certifiably unbalanced, having been driven insane by the assassination of her hero.

The characters are either soapbox mannequins or weirdos, and the plot, involving a never-identified political object, gives symbolism a bad name. This novel is schizy, for good reason.

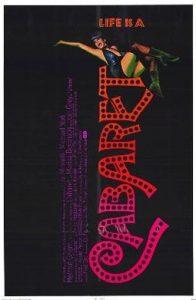

Mailer began composing it when, studying French at the Sorbonne and boning up on classic French novelists, he was inspired by Sally Bowles, the main character in Goodbye to Berlin (1939) by the British novelist Christopher Isherwood. Sally was memorably portrayed by Liza Minelli in the 1972 movie Cabaret.

“Mrs. Guinevere” was born. After some 50 typed pages, he completely ran out of steam and buried her, but she refused to stay dead. Several years later, he resuscitated her—in a different country and different political climate.

In Guinevere, Mailer recreated not Sally Bowles but her blowsier, less interesting older sister. Isherwood’s ambitious singer-actress is a young and hungry man-hunter who is free to roam and roams freely. Mailer’s Guinevere is older, frumpier and, as a mother and landlady, doubly landlocked. “I never go any place,” she complains in the published novel.

If she can’t go anywhere, her creator has nowhere to send her. In limiting his protagonist, Mailer has restricted himself. No wonder she fizzled out fast in Paris.

But she was all that was left after he considered a great many other topics. He gave her another spin, again got nowhere and moved to Hollywood to earn a crust as a scriptwriter. Making absolutely no progress as a novelist, he effectively packed it all in.

He recognized that he was weak at plotting, so he partnered with Jean Malaquais (né Wladimir Malacki), a Polish-born secular Jew, Marxist intellectual and published writer whom he’d met in Paris.

The M&Ms lasted a year in Hollywood. We quit, they said. You’re fired, said Sam Goldwyn.

Either way, it was back to the east coast, back to novel writing and back to Guinevere. “I found something there I could go on with,” Mailer deadpanned.

This was desperation, not inspiration.

For his first novel, Mailer drew on his experiences as a soldier. For its successor, he mined his political ideology, one that he largely borrowed from Malaquais.

Hitching apolitical Guinevere to radical McLeod was a marriage of convenience—for the author.

Mailer wrote Naked and the Dead in a Brooklyn boarding house, and Guinevere is a dead ringer for his erstwhile landlady. Unfortunately, he barely knew her. Not good enough, Isherwood could have told him.

Virtually every character in Goodbye to Berlin had a real-life counterpart.Isherwood modelled Sally Bowles on a fellow British expatriate, Jean Ross, an actress and close friend—close enough for Isherwood to know about her many lovers. When she had an abortion, it was the novelist, not the father, who accompanied her to the doctor. Isherwood also included this highly personal episode in his novel.

Virtually every character in Goodbye to Berlin had a real-life counterpart.Isherwood modelled Sally Bowles on a fellow British expatriate, Jean Ross, an actress and close friend—close enough for Isherwood to know about her many lovers. When she had an abortion, it was the novelist, not the father, who accompanied her to the doctor. Isherwood also included this highly personal episode in his novel.

Isherwood had originals for Sally and a landlady, and he narrates the stories himself. Mailer had only Guinevere. He created no Sally because he apparently knew no one like Jean Ross. His narrator, Lovett, is also weak, a baffled and diffident wannabe writer who doesn’t seem to know how to write, let alone what to write about. As Mailer’s alter ego, his hesitations are ominous. They provide early warnings that plotting may not be his only weakness.

Revolutionary leader McLeod is heavy on Malaquais-inspired talk, light on action. The anarchists in Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent detonate a bomb at Greenwich Observatory in London. The revolutionaries in Andre Malraux’s Man’s Estate (a.k.a. Man’s Fate) plan to assassinate Chinese national leader Chiang Kai Shek. Mailer admired Malraux.

Mailer’s radicals are lecture-hall revolutionaries, pamphleteers. Malaquais himself pronounced, “It is a political tract, not a novel.” His verdict was particularly scathing considering that the novel is dedicated to him.

If Barbary Shore is not a novel, is its author a novelist?

Barbary Shore was nightmarish to write—more accurately, to complete. Expecting nothing more arduous than minor changes and corrections with his final draft, Mailer instead found himself making wholesale changes and adding new material. His new material, however, being new, needed polishing, and he soon enmeshed himself in a vicious rewrite cycle which seemed to be controlled by a mysterious outside force over which he had no control. The entire process had been emotionally tortuous, and in the end, his final draft was still unsatisfactory.

“Towards the end the novel collapsed into a chapter of political speech and never quite recovered,” he admitted, in effect agreeing with Malaquais.

His problem was simple. His imagination was no longer being fed by a world war.

An abundance of people and incidents enveloped Mailer in boot camp and then in active service in the Philippines and as a postwar cook in Japan. He made notes on everyone and everything.

When he created his fictional platoon in Brooklyn, he had detailed descriptions of more than 150 real soldiers, enough for several platoons, and he injected some of his notes, unchanged, directly into his manuscript. This procedure gave him a strong dose of verisimilitude; not surprisingly, several real soldiers recognized themselves in their fictional counterparts. But these verbatim passages tend to be more journalistic than fictional.

Military service gave him his characters and incidents, and his literature courses at Harvard—he devoured writers such as Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Melville, Dos Passos, James T. Farrell, Tom Wolfe—supplied his structure. A dash of Studs Lonigan here, some U.S.A. trilogy there, and the diligent engineering major adroitly converted his numerous notes into his long and compelling, if derivative and sometimes journalistically flat, narrative.

War was kinder to him than peace. Civilian life stiffed, and exposed, him. “I had no characters left. I had used them all up in The Naked and the Dead,” he told biographer Hilary Mills.

As confessions go, this is astonishing. Novelists regularly “use up” their characters. Then they make up new ones. Mailer is admitting that he couldn’t create new characters.

His dilemma is exemplified in Lannie Madison, the bereaved Trotskyite. Although she is similar in age and attractiveness to Sally Bowles, her gaga emotional status renders her a cipher. Conveniently for her creator, she is a non-character.

Characterization was not his only problem. Instead of being a doddle to write like its predecessor, Barbary Shore fought back, viciously. He expected his extreme radicalism to elicit a “shit storm” but no one seemed to notice, let alone care. Far from “perfect,” it was well below the standard expected of professional novelists, let alone one of America’s premier young writers. This novel was amateurish and left him deeply depressed and seriously wondering if he was meant to be a writer.

When he recovered, he came out swinging. His next novel, The Deer Park (1955), on love, sex and politics in Hollywood, would be merely the first of an eight-novel behemoth, a work to out-Proust Marcel. Seven further volumes would each address an edgy theme.

And why not? His Hollywood circle included top producers, directors and actors such as Marlon Brando, Shelley Winters, Edward G. Robinson and Montgomery Clift. They gave him potential characters. He has enough sense to return to the realism he successfully used in Naked and the Dead. Presumably, too, Barbary Shore had taught him a lesson or three about structuring his narrative.

He then repeated the same mistakes he’d made with Barbary Shore

Deer Park’s timid narrator, Sergius O’Shaughnessy, is a war veteran, orphan and journeyman writer who looks a lot like Mike Lovett, the clueless Barbary Shorenarrator. He actually is Lovett. Orphan O’Shaughnessy and amnesiac Lovett are identical twins reared apart.

Although Deer Park posed legal as well as artistic difficulties, Mailer (short version of long and convoluted story) soon produced a final draft acceptable to himself and his publisher. Galleys were prepared. Next scheduled stop: the printers.

Next actual stop: Hades. A return visit. Rewrite Hell.

Between starting and finishing Deer Park, Mailer was more Hipster than Marxist. He was now embarrassed by his nebbish narrator, bored by his harried movie director, and intrigued by the seemingly least important of his three male protagonists, Marion Faye. Petty criminal but moral exemplar, Faye is a precursor of the sex- and violence-oriented “psychic outlaw” championed by Mailer in his controversial 1958 essay “The White Negro.”

Mailer halted publication, started rewriting, added new material and waltzed right into another vicious cycle. Although fully in control this time, he toiled feverishly, draft after Sisyphusian draft.

He stopped revising not because he was finally satisfied. Rather, his publisher’s marketing department, reluctant to miss another big sales window, was having conniptions. Otherwise, like a hamster on a wheel, he might still be at it.

The novel fell far short of his goal. Instead of the mega-masterpiece he needed to restore his reputation and confidence, Deer Parkattracted only mixed reviews. A collateral casualty was his eight-volume whopper, which promptly collapsed under its own considerable blubber. Post-partum, he was physically ill as well as emotionally drained.

He recovered quickly and concocted a new project, a mere trilogy that would include an autobiographical section based on his Russian ancestors. When this bloated concoction collapsed, his well was completely dry.

Publicly, he again talked big, invoking a hurricane-defying home run of a novel or series of novels that would get him into the Pantheon alongside Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, Hemingway and Faulkner, George Eliot, Joyce and Proust and other titans of world literature.

Privately, his hurricane-homer dream was bluster, and he knew it. He had struck out with his second and third novels. More importantly, he was painfully aware that, for him, writing serious fiction was and would continue to be gut-wrenchingly difficult.

“I never want to have again two novels as hard to write,” he decided.

He never would. Instead of hard, he found easy. Easy, as in no rewriting.

Enter Stephen Rojack, hero of An American Dream (1964-65), a breezy narrative that Mailer wrote in eight monthly magazine instalments. Serialization. Just like Dostoevsky, he observed.

Rojack is a grown-up Marion Faye who kills his wife, throws her corpse out of the window and buggers the maid, all of this Hotspur-like hyperactivity occurring well before chapter two is served. More conquests—sexual, pugilistic, psychic—await.

This wham-bam thank-you-mam hipster is a cartoon character, a prose version of single-frame comic-book Pop Art canvasses popular at the time. Rojack is more Roy Lichtenstein than Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Serialization’s real appeal for Mailer was practical, not aesthetic. A firm start date would force him to write about something, anything, and firm monthly deadlines would preclude extensive rewrites. He could finish as well as start a novel without having a nervous breakdown.

Why Are We in Vietnam? (1967), with its motor-mouth hero’s slick but rambling stream of consciousness, is similarly glib. The author’s goal with both novels was the paycheck, not the Pantheon.

These quickies at least got him back to writing fiction, and in 1983, after making noises about his Big Novel, he published Ancient Evenings, a 709-page account of life, sex, death, and then more life, sex and death in olde Egypt. His thrice-resurrected Menenhetet enjoys four lives.

To produce this doorstopper, the author conducted truly prodigious historical research which yielded voluminous notes, Mailerian gold dust. But his supposedly pre-Judeo-Christian Egypt is suspiciously familiar with its telepathy and theories about cancer and God warring with the devil. Menenhetet is Rojack, pre-dated instead of updated, and unrelentingly tedious. The stacks of the New York Public Library were no substitute for a world war. Planned as a trilogy, Ancient Evenings was the sole survivor. No one requested volume two.

Buoyed by massive critical and public indifference, Mailer gave a repeat performance with the even longer C.I.A. novel, Harlot’s Ghost (1991). After 1,282 pages (more with its various lists and notes), he concluded with the three-word threat “To be continued.” It wasn’t. No one wished it had been.

When genuine Naked-and-Dead-like notes did come his way, he won his sole Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Executioner’s Song (1979), on the life, cultural milieu and firing-squad death of real, not fictional, murderer Gary Gilmore.

But he never actually met or spoke with Gilmore. His collaborator, Lawrence Schiller, did, and it was his notes that Mailer used. He also connived at marketing the book as fiction despite knowing that that label was itself a fiction. His “true life novel” is certainly Pulitzer quality. Its genre is iffy.

None of Mailer’s wives, ex-wives, nine children and a small platoon of divorce lawyers went hungry. His celebrity status boosted sales of his books, fiction and nonfiction alike, whether good, bad, indifferent or preposterously oversized or overhyped, or actually read.

Bellow Going With the Flow

Saul Bellow soared when, and where, Mailer faltered. After relieving himself of his bedridden hospital patients, Bellow created Augie who, in love with Esther, goes to Mexico with her equally beautiful sister Thea, then flits to among others, heiress Lucy, waitress Willa and chambermaid Sophie before marrying Stella and ending up in, where else, Paris.

Bellow’s picaresque hero is, mutatis mutandis, Sally Bowles. In a further parallel to Goodbye to Berlin, Augie helps his platonic friend Mimi through her potentially life-threatening abortion.

Augie introduces himself in the novel’s famous first sentence: he is a Chicago-born American. Only later do we learn that he is Jewish, very Jewish. In the next sentence, self-educated Augie refers to the Greek philosopher Heraclitus.

Buckle up.

In an extraordinary set piece, Bellow’s urban protagonistis riding a horse, an eagle on his arm, on a mountain, in Mexico, helping his monomaniacal girlfriend Thea train her eagle Caligula to catch lizards.

When a lizard bites back, Caligula behaves like a pussycat, and Augie comes to grief, falling off his horse, which was itself falling, and breaking his arm. For good measure, the horse kicks Augie in the head, knocking him unconscious.

Despite serious injuries, hospitalization is out, for author and character alike. Treatment by a local doctor suffices and Augie is soon going to new places, meeting new people, receiving lots of advice, and nabbing new girlfriends.

For material, the author borrowed when he could, and stole when he couldn’t.

Thea and her lizard-hunting eagle? He lifted the entire episode from magazine articles. Typically, he schnorred closer to home—sometimes too close.

Augie’s brother Simon has a wife, and a pregnant mistress. Bellow’s brother Maurice (a.k.a. Moishe) had a wife, and a pregnant mistress. The novel exposed Maurice’s secret, causing a serious rift between the brothers. (Sally Bowles’ abortion similarly strained Isherwood’s relationship with Jean Ross.)

Bellow based Augie on a childhood friend, Charles August, who was fond of proclaiming “I have a scheme.” The Augusts also gave him “Grandma” Lausch and Augie’s institutionalized brother George (“He was born an idiot.”).

For Augie’s “superior” man William Einhorn and his entire family, Bellow drew on the Freifelds, a prominent Chicago family.

Augie is mostly Bellow himself. Augie, a merchant mariner, is on a ship that is torpedoed, propelling him into a lifeboat alongside Basteshaw, a homicidally maniacal scientist. Bellow was a merchant mariner; he based Basteshaw on an artist he knew.

To capture Augie’s multifaceted world, Bellow had to raise his stylistic game: Street Chicago. Jewish Chicago. Great Books Chicago. Lyric Chicago. Comic Chicago.

When a long-lost friend asks Augie what he has been doing, he replies, truthfully, “I wash dogs.”

Augie’s milieu is predominantly Jewish and includes several east European immigrants who don’t know their Heraclitus from their halvah, and with Yiddishisms their English is tinged.

“Eat I can where I want,” says Augie’s cousin, Five Properties, whose leitmotif is “five prope’ties, plente money.”

Another character declares, “I could not find myself in love without it should have some peculiarity.” This is Augie himself, sounding like the greenhorn he wasn’t.

Bellow’s native languages, in a childhood household that was quadrilingual, were English and French. His parents, two brothers and sister spoke Yiddish and Russian. In Augie March, the elder Coblins, Augie’s aunt and uncle, speak Russian to their children, who reply in English. Grandma Lausch and Augie converse in Yiddish.

Bellow’s mother, the rabbi’s daughter, kept a kosher home and raised young Schloime as a fringe-wearing Orthodox Jew. His father, Abraham Bellow (ne Belo), was a brawler and a bootlegger, more Isak Babel’s Odessa gangster Benya Krik than shtetl schlemiel. His father’s son, Augie steals textbooks and pockets tips intended for waiters. Shrewd, assertive Grandma Lausch also hails from Odessa.

Is Augie March hard going? Too long? Too exuberant? Bellow shrewdly took stock. “I had to tame and restrain the style I developed in Augie March in order to write Henderson and Herzog,” he explained.

But his new novel showed him the way. He based his non-Jewishly-tall non-Jewish hero of Henderson the Rain King (1959) on his New York landlord, inserted plenty of himself, and concocted a fantastical Africa he had not yet actually visited. It worked. Even Norman Mailer was begrudgingly impressed.

After Henderson the Goy, he found a Jew to write about. Bellow was born in Montreal, son of an adoring religious mother and a not always law-abiding father. He had peritonitis as a child, necessitating a long stay in a Catholic hospital.

Ditto Moses Herzog.

Saul Bellow was cuckolded by his best friend.

So was Moses Herzog.

With its pistol-totin’ letter-writing hero, Herzog (1964) is a meshugana novel about a possibly meshugana man composed by an experienced writer in full control of his sanity as well as his artistry.

Arrested after a minor traffic accident (undone by an archaic but unfortunately real pistol in his not entirely innocent possession), Herzog gives the policeman his address book. Parisian red-leather, Bellow specifies. It could have been a gift from Augie.

Herzog is Bellow, Bellow is Herzog. The Humboldt in Humboldt’s Gift (1975) is writer Delmore Schwartz, and Charlie Citrine is Bellow. In his final novel, Ravelstein (2000), the eponymous hero is political philosopher Allan Bloom, and Chick represents the author. The template Bellow used in most of his novels originated with Augie March.

Mr. Sammler’s Planet (1970), with its cantankerous Holocaust-survivor hero, gave him a spot of Mailerian bother. “It was out of control…. Sammler isn’t even a novel. It’s a dramatic essay of some sort, wrung from me by the crazy Sixties,” Bellow conceded, using the same terminology that Mailer and Malaquais applied to Barbary Shore. But Sammler’s caustic views do not overwhelm his novel in the way that Trotskyism suffocates Barbary Shore. (Trotsky appears in Augie March, in an unmemorable walk-on). The author’s misgivings notwithstanding, Sammler won the National Book Award.

Mr. Sammler’s Planet (1970), with its cantankerous Holocaust-survivor hero, gave him a spot of Mailerian bother. “It was out of control…. Sammler isn’t even a novel. It’s a dramatic essay of some sort, wrung from me by the crazy Sixties,” Bellow conceded, using the same terminology that Mailer and Malaquais applied to Barbary Shore. But Sammler’s caustic views do not overwhelm his novel in the way that Trotskyism suffocates Barbary Shore. (Trotsky appears in Augie March, in an unmemorable walk-on). The author’s misgivings notwithstanding, Sammler won the National Book Award.

Lithuanian Landsmen

Mailer’s New Jersey-born mother Fanny (née Schneider) brought doting Jewish motherhood to new extremes. His Johannesburg-born British-accented father Isaac Barnett (Barney) was a dandy and a gambler who, like Bellow’s father, was more wide boy than Pale of Settlement schlemiel. His grandparents came from the same region of Russia (present-day Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus) that Bellow’s family had found inhospitable.

Mailer dutifully attended Hebrew school and had a bar mitzvah at which he invoked Spinoza and Marx more than Moses, foreshadowing his pot-smoking, bourbon-swilling, wife-stabbing, head-butting future.

“Nice Jewish boy?” That was the last thing he wanted to be, or be seen to be. But he did not deny being Jewish and he didn’t stint on Jewish characters, at least in his early fiction.

Ethnic balance required one Jewish soldier for Naked and the Dead. He supplied two, although both are minor figures. Rojack and Sam Slovoda (“The Man Who Studied Yoga”) are part Jewish and part Irish, as is the hero of his detective potboiler, Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1984).

He went full-Irish in his 1968 movie Beyond the Law in tough police lieutenant Francis Xavier Pope, portrayed by writer/director Mailer himself. He has finally buried amnesiac Lovett and orphan O’Shaughnessy, but his new alter ego is, like Rojack, more caricature than character.

Mailer’s Russian ancestors failed to supply him with a sufficient quantity of raw, useable data. But even if he had obtained an abundant supply of notes, his emotional links to his ethnic roots were thin and, given his artistic limitations, his characters would have been inauthentic, mere Rojacks with east European accents. He was never a contender to out-Malamud Bernard or out-sing Isaac Bashevis.

Matrimonial statistics, while not conclusive, are suggestive. Four of Bellow’s five wives were Jewish, whereas all of Mailer’s brides after his first were non-Jews.

They’ll Always Have Paris

Mailer and Bellow traded places as prized novelists, a process that began in Paris.

The characters in Barbary Shore, like hospital patients, rarely leave their cruddy rooms and don’t stray far from home when they do. Bellow’s picaresque hero is constantly on the move emotionally as well as geographically.

Mailer promptly jumped into the claustral hole out of which Bellow leaped at the earliest opportunity. A year before Ralph Ellison’s sewer-dwelling Invisible Man, Mailer installed Guinevere in the basement flat of her boarding house.

Paris may have been the place, but timing was actually more important than geography.

Mailer could have been anywhere in the world when he read Goodbye to Berlin, whereasBellow’s epiphany was specifically Gallic. But he was ready to blow. His first two novels were too “correct,” and his new effort was no better. “I must get rid of the hospital novel—it was poisoning my life,” he lamented. Change was inevitable, even imminent.

If the street cleaners hadn’t opened the hydrants that fateful day, something else, almost anything else, would have triggered him. Ah, regardez cette baguette. I can write like that baguette, soft as well as crusty. If he’d been in Jerusalem, or Brooklyn, the catalyst could have been a bagel.

Mailer’s chronic struggles as a novelist, and Bellow’s blossoming after he discovered his voice, occurred in Paris at critical times in their careers. But the outcome—Mailer’s fall, Bellow’s Nobel-bound rise—would have occurred even if they had gone to Poughkeepsie.

###